Originally posted by Patrick McGee in the Financial Times

© PR handout

Walmart has been working with Ossia, a Washington-based company that has developed “distance charging” technology it calls Cota — or Charging Over The Air.

Ossia sends radio frequency power from a central transmitter to multiple devices — including electronic shelf labels each equipped with a small receiver — without any direct contact to cables or a charging pad. The Cota Tile, for example, transmits 20 watts. Devices around a metre away receive 6 watts, at two metres that falls to about 2 to 3 watts. Electronic shelf screens, which require little power, were an obvious first application to test.

“These are the first-ever electronic shelf labels with no battery — they receive power all the time,” said Hatem Zeine, chief technology officer at Ossia. “This means you can make receivers that are thinner, that last the lifetime of the display.”

Another Ossia device, the Forever Tracker, is being used by Walmart and T-Mobile to keep tabs on packages, crates and pallets within distribution centres. The tracker uses a battery that Mr Zeine said would never need to be replaced — a major claim, albeit on a small scale relative to, say, a smartphone.

While “passive” trackers powered by radio frequency already exist, Ossia said its wireless technology could constantly charge battery-enabled “active” trackers — the kind that need extra power to send a continuous, more easily detected signal.

“Batteries were invented when Napoleon Bonaparte was alive, in 1800,” said Mr Zeine. “And every battery ever made has the same flaw: it runs out of power at some point. That’s where Ossia comes in: we can deliver power that feels like WiFi.”

Walmart’s Cameron Geiger, a supply chain executive, said in October the technology had “unique potential to bring tremendous efficiencies to the logistics and supply chain process”.

Making the leap from limited commercial applications into the consumer market is likely to prove difficult. But the Forever Tracker received approval in October from the US Federal Communication Commission. In the same month, Ossia signed a licensing deal with Galanz, the world’s biggest maker of microwave ovens. Galanz will embed transmitters in its products so that they can charge up an emerging ecosystem of other appliances.

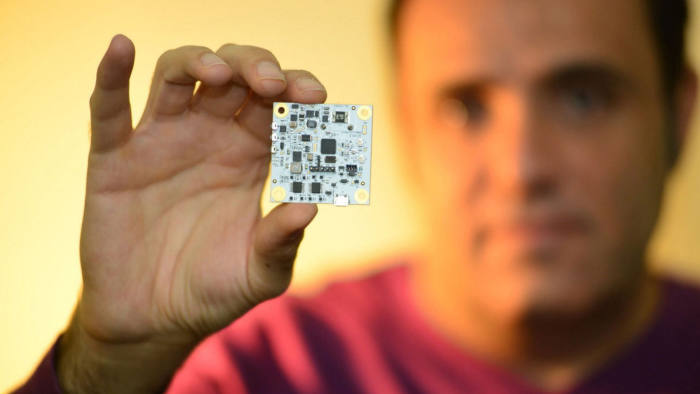

Another start-up, Atmosic Technologies in San Jose, is a computer chip manufacturer driven by the vision of what its chief executive David Su called a “battery-free IoT revolution”.

Mr Su, a former Qualcomm executive and radio frequency expert who co-founded Atmosic in 2016, said the start-up was taking a two-step process to eliminate batteries in simple gadgets such as personal tracking devices, wearable wristbands and remote controls.

First, it uses energy-saving designs to lower the power usage needed for these devices to operate. Then it relies on “harvesting energy” from nearby sources to power them.

Atmosic has powered a wireless keyboard, for instance, that converts energy from two sources: mechanical energy from the user tapping the keys, and by taking radio frequency power from a nearby monitor.

Similarly it can power a smart lock that, through its Bluetooth connection, receives energy from a user’s smartphone. The lock is equipped with a small battery — but one that never needs to be replaced.

Srinivas Pattamatta, vice-president at Atmosic, said eliminating the need to replace batteries could offer businesses savings not just in battery costs but in labour.

“An average US hospital with 1,000 beds has 50,000 assets — boxes of hospital equipment they have to track,” he said. “Each of those has a tracking solution. If you need to replace [the batteries]every six months it’s like having to paint the Golden Gate Bridge.”

This month Atmosic raised $29m in its Series B funding round, led by Sutter Hill Ventures, and it is now producing its first products.

“This is the first time anyone has ever put a whole system together that can actually be used on a massive scale,” said Stefan Dyckerhoff, partner at Sutter Hill, a private equity firm.

Eventually, Mr Dyckerhoff said, the hope is that more complicated devices could take wireless sources and convert them into power. The Bluetooth signal to a set of Apple’s AirPods headphones, for instance, is more powerful than necessary to maintain a connection to an iPhone, he said. The excess energy could be directed into keeping the headphones charged.

“There is excess energy all around us,” he added. “From your phone, from the WiFi in your office. We can harvest that energy so devices can power themselves. It’s kind of wild.”